Playing chess is somewhat alien to many children today, a game that was once quite widely played in Britain is now perceived by some as elitist. However, in schools – particularly in primary education – there is real educational value in learning the game, including opportunities to broaden the curriculum.

With schools continually being assessed and ranked on performance, there has naturally been a shift in education towards “teaching to the test” and a focus on literacy and numeracy skills. Creativity in schools has been pushed to the outskirts, and in some schools is at risk of becoming lost.

Schools are expected to provide a broad and varied curriculum while championing attainment, an added pressure for educators already facing challenges with budgets and workloads. Broadening the curriculum and adding creative elements is a fantastic way to engage pupils in their learning, but solutions are needed to support teachers in creating rich and creative learning experiences that can have a positive impact on results.

The educational value of chess

Chess is a very engaging and creative game which is also useful in acting as a vehicle to support the delivery of core skills. Numerous studies have suggested that learning and playing chess has a positive correlation with attainment (see for example, Sala & Gobet, 2016; Rosholm et al, 2017; Nicotera & Stuit, 2014).

Moscow is an example of a city that has already recognised the value of chess in the classroom, having made the game compulsory for every child for one hour a week in primary education. In Russia chess is culturally very popular, so the implementation of the game in lessons has the potential to be more seamless than perhaps might be the case in the UK, but this should not detract from the potential value it can bring.

At my school, Cwmlai Primary, we have been trialling chess clubs during lunchtimes as a way to engage pupils and teach them new skills. I have a personal interest in chess so have the benefit of prior knowledge, but other members of staff are also learning the game. We are constantly looking at ways of softly introducing chess to both teachers and pupils – and this is where technology can be extremely useful.

Utilising ed-tech

Resources for any subject can be a challenge to find, but the growth in online platforms and access to apps has eased the pressure on teachers. We were lucky enough to win an interactive panel in a competition last year which we now use in conjunction with our class tablet devices to access a wealth of free-to-use chess resources to get started with the game. As it is a lunchtime club this is particularly useful as we can have access to the resources in seconds, saving valuable time and allowing us to get on with the business of playing and practising new strategies.

There are an array of apps available in the app store and lots of guidance online for teaching chess. Teachers and pupils can learn together – just because a teacher might not know much about chess personally, does not mean that this should be avoided.

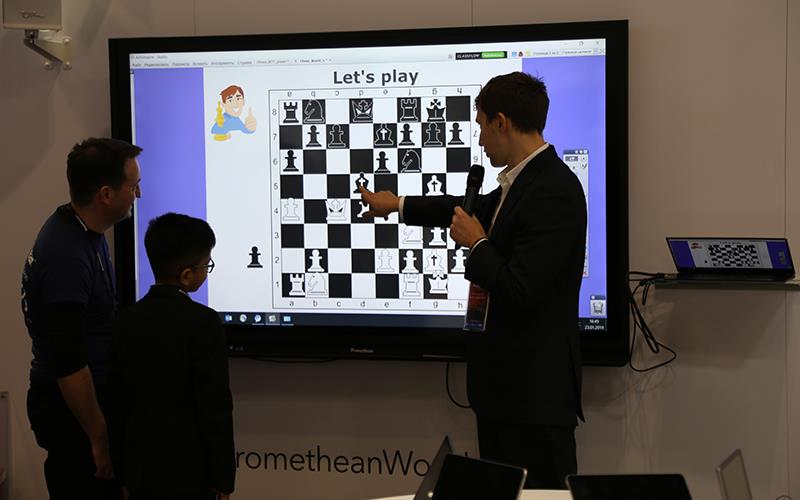

Many of the apps available are games, so are really enjoyable for classes to get started. We often see pupils learning a great deal without actually realising it and it can be a really effective way of engaging pupils with a subject. Using apps on our interactive panel is a great way to model concepts to the whole class and once pupils are comfortable with the concepts demonstrated they can use them with activities on tablet devices or using real chess boards.

Learning check: Technology is put to good use during the chess lessons and matches at Cwmlai Primary School (image supplied)

Links to curriculum subjects

Chess has synergies with a number of school subjects that are not completely obvious when the game first comes to mind, but it is because of these synergies that chess is so useful for cross-curricular learning.

Maths is used in every game whereby opponents write down the scores of the game and add them up – algebra can even be demonstrated through the different values of chess pieces. Again, through this game-based style of learning pupils often demonstrate greater levels of engagement. Chess is also fundamentally aligned with coding whereby moves are described as coordinates and written down, following similar principles to coding exercises. Pupils with knowledge of chess often experience a greater understanding of coding.

Critical and analytical thinking are also key skills that pupils develop through chess, as players have to assess every one of their own moves and potential moves, as well as their opponents’ moves.

In discussions between opponents after the game verbal reasoning comes in to play, and this can be particularly beneficial when pupils mirror their game to the panel at the front of the classroom to explain what happened (an exercise which also increases their confidence).

In the early stages of learning the game pupils can find losing quite challenging, but we often witness enhanced resilience as a result of losing a game and pupils wanting to learn more to understand what they can do differently next time. Whole class discussions and peer assessment on an interactive panel at the front of the class (or with small groups around an iPad) can be a great way to cultivate everyone’s ideas and to encourage pupils to learn from one another.

Supporting pupil wellbeing

In addition to the range of skills developed through learning chess, the game is inclusive and can have a positive impact on pupil wellbeing.

Chess is accessible to a range of ages and abilities, capturing the attention of more able and talented pupils as well as those with additional learning needs.

Pupils with additional learning needs have been unrecognisable in chess lessons with the level of skill and attention shown – it is quite remarkable to see. Chess can break down barriers between pupils and encourage them to become familiar with playing against different people, not just those in their friendship groups; pupils gain an added sense of self-esteem and confidence. We have witnessed strong interest in the game from both boys and girls which can sometimes be a challenge with other subjects or activities.

Exploring opportunities to broaden the curriculum

We had our doubts about trialling chess clubs but coupling the game with technology has allowed us to introduce it with a low risk and low cost strategy – one I would highly recommend to other schools. If we continue to see a positive response, we will invest in chess boards and there are formal programmes available for the implementation of chess that we can consider.

Chess has shown the potential to strengthen pupil engagement, wellbeing and attainment – proving itself as a valuable proposition for us. Though educators in the UK are relatively unfamiliar with the game, I am a firm believer that the best of teaching innovation comes from pushing boundaries and trying new things and ed-tech has made chess more accessible than ever. The engagement and cross-curricular skills fostered through chess could make it an excellent opportunity for schools looking to broaden their offering and engage pupils in a different way.

- Elizabeth Scott is deputy headteacher at Cwmlai Primary School in South Wales.

Further information & research

- Do the benefits of chess instruction transfer to academic and cognitive skills? A meta-analysis, Sala & Gobet, Educational Research Review, Vol 18, May 2016: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2016.02.002

- Your move: The effect of chess on mathematics test scores, Rosholm, Bjørnskov-Mikkelsen, Gumede, PLOS, May 2017:

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177257 - Literature Review of Chess Studies, Nicotera & Stuit, Basis Policy Research, November 2014: http://bit.ly/2JUBMGc