With the new film Wonder (based on the best-selling book by RJ Palacio) in cinemas across the UK, disfigurement is a hot topic and one that might be making its way into the classroom.

Unfortunately, we know that almost half of young people with a disfigurement are bullied at school and the vast majority of people – nearly 90 per cent – say their primary school did not succeed in stopping the bullying.

Often it is difficult for headteachers and school staff to feel confident enough or to have the expertise to start important conversations about visible difference. Yet knowing how to address issues around appearance matters, because whether you are teaching everyone about inclusive attitudes, or supporting a pupil who looks “different”, good intentions and common sense don’t always lead to best practice.

Research shows that the things we think we should do – prohibit staring, use kind euphemisms for a child’s unusual appearance – often turn out to be unhelpful. Whereas discussing appearance and inclusion in ways that invite and allow for a range of views can be incredibly effective.

You may not have a specific youngster in mind, particularly if you’re in a small school, but it is important for all children to learn about disfigurement. This doesn’t just benefit those with a visible difference. Children who have a healthy perspective regarding appearance are much better equipped for life, where they will encounter colleagues, customers, managers and neighbours who may look “different”. Developing these social skills can also lead to higher self-esteem and an increased capacity to understand and learn.

After Changing Faces ran a recent workshop at Ravenstone Primary School, we received 60 letters from pupils. One child wrote: “I never realised how hard it must be. I thought people who looked different were different from us, so we had to treat them differently. But now I know that they’re the same as any other child.”

How common is disfigurement?

Around 86,000 children across the UK are estimated to have a disfigurement, that’s one in 124 in the under-16 school population. That can be a mark, scar or condition that affects the appearance of their face or body. Disfigurement can take many forms: birthmarks, skin conditions such as eczema and acne, vitiligo affecting skin pigmentation, scarring from burns or a dog bite, or conditions present at birth affecting the head and face, such as a cleft lip and palate. So how do you start to promote an inclusive learning environment in your school?

The Equality Act (2010) requires schools to ensure that no child is disadvantaged at school because of a disfigurement, and to increase all pupils’ awareness and acceptance of differences. This includes unwitting discrimination which may have “good intentions” behind it, such as “protecting” a child with a disfigurement who is keen on drama and acting, by discouraging them because of the fear that this cannot be a comfortable or successful path for them.

What does best practice look like?

Differences and commonalities: When differences among all pupils and staff are celebrated, a pupil with a disfigurement won’t feel so different. Giving pupils the opportunity to talk about who they are, both on the outside (how they look) and on the inside (their personality, likes/dislikes), is a great way to explore appearance and difference. Changing Faces has produced Wonder-related resources for headteachers and teachers to explore and celebrate difference across their school in different ways (see further information).

Discuss and disagree: Allow children to talk about things that they find different so that they can explore their ideas and attitudes. Statements such as “we are all equal” without context and explanation can have the opposite effect. Use school values or class rules as a starting point for discussions about respect and whether everyone feels equally welcome in your school.

Challenge stigma and use positive images: Positive representations of people who have a visible difference are a powerful tool in supporting pupils to challenge negative stereotypes. For example, teenage YouTube star and winner of Junior Bake Off 2016 Nikki Christou (who broadcasts as Nikki Lilly), has a condition called arteriovenous malformation (AVM), which affects the appearance of her face. Nikki vlogs about topics including baking, make-up and the impact of bullying.

Use matter-of-fact language: Written and spoken language around appearance and disfigurement is often characterised by emotive and judgemental vocabulary – so much so that this can seem natural and right. Matter-of-fact language to describe and discuss appearance and difference works better. For example, use “severely burned” and “burns survivor” instead of “horribly burned” or “burns victim”.

Zero tolerance of bullying and harassment: Appearance-related bullying must be stopped in the same way that any other bullying incident would be stopped, with the focus firmly on the bullying behaviour and not the “cause”. School staff can – and must – intervene every time someone in your school is harassed or bullied. While you can’t make all children be friends, they must learn how to show respect at all times. When they find themselves in the role of bystander, they need to understand their choices besides doing nothing. Some children need help to develop ways to manage their impulses to be hurtful or “have a laugh” at someone else’s expense. All this works best in a school with a strong ethos of belonging and respect.

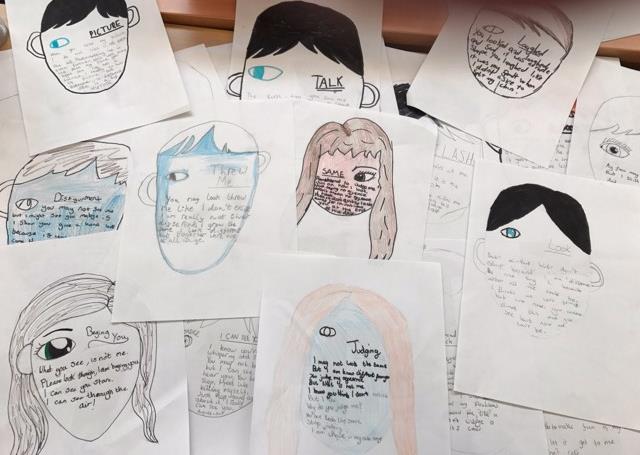

Talking about difference: Pictured are examples of work produced by pupils during a Changing Faces schools session

How to support a pupil with a visible difference

Don’t give a “talk” about a specific child: Staff often believe that their class or the whole school will be less dismayed and will stare less if they have more information about a child with a disfigurement. But children’s curiosity is an important driver for getting to know each other. If children already think they know about this unusual-looking child, and if this child has already been made more “different” through being the subject of a talk, their classmates may be less inclined to play with them.

Confident staff with high expectations: Ensure all members of staff feel comfortable and confident talking about all kinds of difference. It is often the fear of saying the wrong thing that can stop a teacher from taking action or starting a discussion with their class. Children will also pick up on any member of staff who feels uncomfortable, so create opportunities for staff to explore their ideas and discuss their feelings about appearance and disfigurement.

Having something to say: If a pupil has something that makes them appear “different” to others, make sure you work with them to discuss what they want to share about their appearance. Support them to take the lead in their own lives and to respond confidently to questions or comments about their appearance from other pupils. If the child is not ready for this, ensure all staff know how to model effective responses to other pupils’ curiosity using the “explain-reassure-distract” technique. For example: “Michaela’s got scars from a fire but she’s fine now. Maybe you’d like to go and introduce yourself as you’re both new here.”

Never patronise: Above all, remember that pupils with a visible difference should be subject to the same behaviour expectations as the rest of the school.

Advice for when talking about difference

- If you see someone who looks unusual to you, you might look for a long time, or more than once before you even think about it. If this happens, give the person a friendly smile to show you don’t mean to be hurtful.

- Many people have marks, scars or conditions that change the way they look, but we notice some more than others. Think about different features you or your family might have – maybe you have a birthmark, or eczema, or a scar? Or you might know someone who has hearing aids, or some missing teeth? These things don’t usually affect what you like to do, or how you friendly you are, or how you feel inside. The same is true for people who have differences that are more noticeable.

- If you feel worried about what to say to someone who looks different, try starting off with some things about you. Tell the person what you like to do, or about one of your pets, or your favourite TV show. The other person will probably join in, or you can ask them about the things they like and enjoy. Talking about what makes you both happy is usually a good way to start with someone new.

Conclusion

We hope the release of Wonder may help to prompt discussions in class and raise awareness. Young people are under such pressure to look a certain way – we want to move towards a society that values difference so that everyone can live confident and happy lives. If you would like to download school resources and/or book a Changing Faces workshop for your school, please visit our website.

- Alexis Camble is schools outreach officer at Changing Faces and Dr Jane Frances is the former policy advisor in education at the charity: www.changingfaces.org.uk

Further information

- For the Wonder-related resources, go to http://www.changingfaces.org.uk/resources/education/teachers/wonderresources

- Wonder film trailer: http://bit.ly/2nTOsUa