The introduction of the upper pay range (UPR) in 2000 has had a long a chequered history. It is only recently that the errors of its introduction are coming home to roost.

Access to UPR has always been on the basis “that the teacher’s achievements and contribution to an educational setting or settings are substantial and sustained”.

This progression criterion has never been defined in regulation (School Teachers’ Pay & Conditions Document – STPCD) and left schools defining their own understanding of the wording. Neither has the second criterion for access been defined, i.e. “that the teacher is highly competent in all elements of the relevant standards”.

The issues

At the time of the introduction of threshold assessment some headteachers and school leaders avoided making difficult decisions defining the access criteria to the UPR. This led to some school leaders avoiding hard conversations. Instead they placed staff automatically on the UPR.

This continued in future years with progression up the UPR with little or no examination of the “substantial and sustained” contribution of those staff.

School leaders inheriting this situation are now having to deal with the consequences. Some UPR3 teachers take the salary and, while being good teachers in their own classroom, make little contribution to whole-school development or training. Other teachers in the school staffroom such as recently qualified teachers, quite rightly, consider the situation to be unfair as they continue to make huge contributions to whole-school life.

At this point it is only reasonable to say that in some schools it has not been made clear to teachers the expectations that the school has of them. It is difficult then for them to match up to those expectations.

For them, the definition of “substantial and sustained” continues to be shrouded in mystery. Some UPR3 staff have used this lack of clarity over the years to claim that being held to the “contribution” criterion is unfair.

When making pay and conditions recommendations to the previous coalition government, the School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB) attempted to clarify the criteria for access to the UPR. They defined them to be:

- “Sizeable and sustained achievement of objectives, appropriate skills and competence in all elements of the Teachers’ Standards.”

- “The potential and commitment to undertake professional duties which make a wider contribution (which involves working with adults) beyond their own classroom.”

In an attempt to support colleagues and give clarity, many schools are now defining the threshold access criteria in their pay policies by combining the STPCD criteria with the STRB clarification above.

Access arrangements to the UPR changed in 2013 from a national system of application to a school-based system. At the same time, schools were revamping their appraisal processes to take account of performance-related pay. A key element of both processes has been the definition of the expectations of teachers across both pay ranges.

These “Career Stage Expectations” give teachers clarity. They give teachers a clear understanding of the expectations of them by the school instead of having to guess.

They also understand how they may be asked to evidence the typicality of their day-to-day practice against such expectations. Nationally this is becoming an integral part of the appraisal review process.

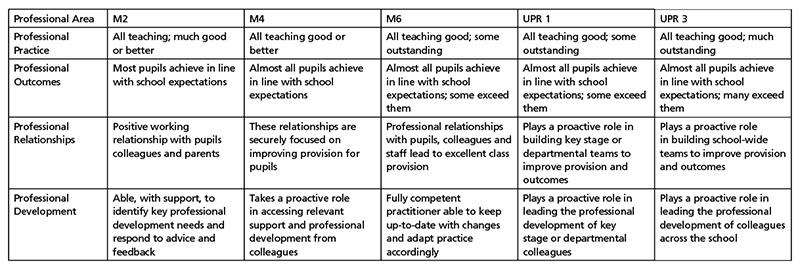

There are many examples on the internet of career stage expectations developed by individual schools. These documents are often laid out in tabular form tied closely to the Teachers’ Standards that were issued in 2012.

Each column in the table represents a stage in a teacher’s career. This is usually aligned to their position on the pay scale or, alternatively, the number of years a teacher has been practising (see the example below).

Aiming high: Just one example of how a school’s Career Stage Expectations might look

The process

You can also find a range of systems and documents supporting teacher applications to the UPR on the internet. These will give you a basis for developing or tweaking your own threshold assessment process.

There is no requirement for schools to operate an application form system for access to the UPR. However, many schools find this supportive of the process for both the teacher and the school leader assessing the threshold request. There is no requirement for teachers to produce a wide portfolio of evidence.

The school’s pay policy should include the process for applying to cross the threshold, including the progression criteria, evidence that will be used, and how the threshold assessment will be handled. This clarity supports the teacher in their application and develops their understanding of the responsibilities attached to being paid on the UPR.

Although teachers can apply at any time during the academic year (once a year max), most schools include a deadline in their policy by which a teacher must indicate that they wish to be considered for progression.

The threshold application process is normally linked to the appraisal cycle. A logical deadline date for applications could be November 30, giving time after the end of the annual appraisal round (October 31) to consider the outcomes of individual appraisal meetings.

As it is a voluntary process teachers should make their headteacher and/or appraiser aware that they wish to be considered for progression on to the UPR.

It is also no longer a requirement that teachers need to be paid on a particular pay point, previously the top of the main pay range (MPR), before they can progress to the UPR.

Progression to the UPR is linked to performance using appraisal reviews and as such an “M4” teacher, for example, may in discussion reveal significant evidence that they meet the criteria to progress through the threshold.

In the example below, a teacher may have played a significant and on-going part in proactively “leading the professional development of colleagues across the school” over a considerable length of time. That colleague will be able to consistently evidence the other expectations of a UPR teacher as defined by the school during the previous appraisal round and as such may match the school’s criteria for progression to the UPR.

The challenge

The challenge to schools and UPR teachers is finding opportunities to allow those teachers to fulfil their obligations, i.e. their contribution to whole-school development and improvement.

The challenge for school leaders is to hold UPR teachers to account for their position on the pay range. This issue is raised by heads and principals at every appraisal and performance-related pay training event I host around the country.

It is usually phrased as: “I have X number of UPR3 teachers in my school who are good in their own classrooms but make little or no contribution to the whole school. They’re often the people least engaged with other colleagues. Some commit little extra time to school development. What can I do?”

I would suggest there are three options to consider: First, are there opportunities for these teachers to contribute their skills for the benefit of the whole school? For example, the good UPR3 teacher whose use of data to support learning and progress in their own class is excellent – are they given opportunities to share their expertise? Can they mentor other teachers who do not have this expertise? Developing the use of data is often part of a school improvement plan and this teacher could use their skills to support this element of the school’s development. This could include, for example, setting up workshops for staff who have identified in their appraisal reviews the need for training in this area.

This could then be followed up by the UPR3 teacher working alongside and supporting the teachers as they put into practice the training they received and monitoring its effectiveness in the classroom. With further follow-up workshops this could be a significant contribution to school development and if sustained over the year would give the UPR3 teacher the opportunity to fulfil the terms of their position.

Yes, leaders and teachers all need to be creative here. UPR (and other teachers!) have skills and expertise that deserve sharing. The net effect will be to the benefit of the school.

The second option is that of capability. Is the teacher capable of delivering substantial contributions beyond their classrooms over a period of time? If they’re not then they need support to be able to do this. If they are still unable to do this, the school’s capability procedure would then come into effect. The important point here is that some teachers need support to work alongside colleagues. It may not be a natural activity for them but they do need to make their contribution.

Third, it may be the case that the UPR teacher does not wish to contribute to whole-school improvement. They refuse to fulfil the requisites associated with being a UPR teacher. In this case it then becomes a disciplinary process issue. In these last two options school leaders would be well advised to take advice from their HR provider.

A question also raised is: “Can the teacher move back to the main pay range?” The simple answer to that question is: “No they cannot.”

Sara Ford, a pay, conditions and employment specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders, explained: “In December 2015, the secretary of state asked the STRB to consider introducing into the STPCD the flexibility for staff to move from the UPR to the MPR (something which is currently not permissible). The STRB, having considered all of the evidence on the issues in 2015/16 recommended that there was no need to introduce this flexibility, and the secretary of state agreed with that recommendation: a decision endorsed by ASCL.

“We are of the view that where employers have concerns about an employee’s performance they should be providing the required support through the performance management/appraisal policy and then, if appropriate, the capability policy. It would not be appropriate for staff to be ‘moved’ to another pay range because of concerns about performance.”

She adds that “staff are of course free to apply for vacancies that arise in the school on the MPR (where a policy does not enforce pay portability) as part of normal vacancy-filling procedures”.

However, school leaders would be advised not to consider a colleague who wishes to do that as a way of avoiding whole-school contributions. HR and legal advice should be taken if this is a possibility to avoid future claims against the school.

It is not the fault of those UPR3 teachers who now have to validate their position on the pay scale. Many have been put in this position historically. It is now time for school leaders to find ways to work with those colleagues so that all UPR3 teachers are making substantial and sustained contributions to the development of their colleagues’ skills for the benefit of all learners.

- Brian Rossiter is a former headteacher, an education consultant, appraisal trainer and chair of the L.E.A.P. MAT in Rotherham.

Further information

Effective teacher review and appraisal practices, Brian Rossiter, Headteacher Update, September 2017: http://bit.ly/2y5HEaM