With the end of the academic year fast approaching, most of us are planning what staff professional development might look like from September.

There are many changes taking place in the coming months in this space – not least the new statutory Early Career Framework implementation from September (DfE, 2019, 2021a), which affects both early career teachers (ECTs) and their mentors, and the new National Professional Qualifications (DfE, 2021b).

As a headteacher or senior leader responsible for CPD, we often think of the professional learning undertaken by our staff as something that “they” or “we” are going to be doing – with each member of staff undertaking a programme of professional development specific to their needs, career and responsibilities for the year ahead.

But alongside this, we also recognise that our school consists of “us” all coming together to create a learning environment that provides the very best experiences for the children.

Therefore, I encourage you to pause briefly as you plan next year’s professional development for staff and consider how “their”, “your” or “our” learning experiences will affect “you” as a leader, including your planning and your leadership style.

What does this mean for CPD?

Let me take you on a brief journey to explain why this matters and what you need to do.

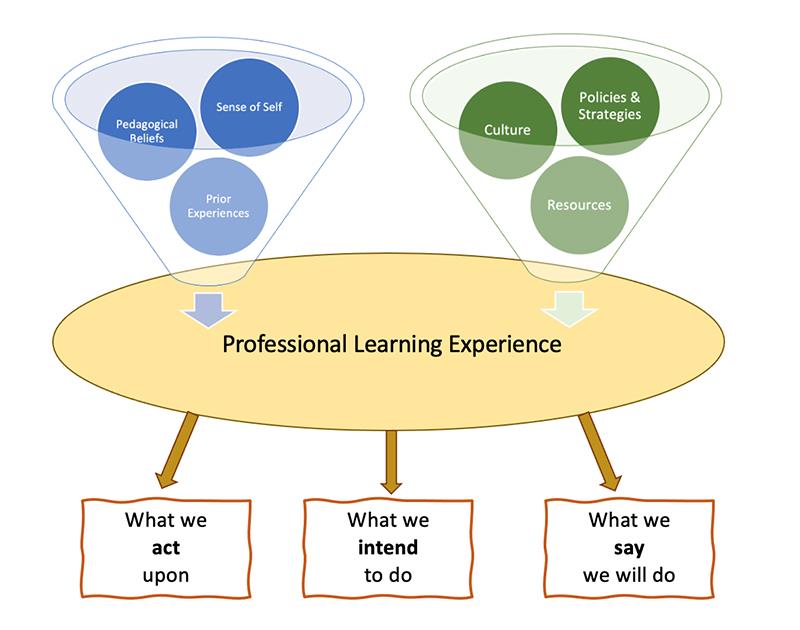

When each individual member of staff is part of a professional learning experience (e.g. INSET, a course, something they read, a coaching session), they have two main sources of influence affecting them.

The first comes from within: A combination of their sense of self and identity, their personal and pedagogical beliefs, and their prior experiences. These mix together to form a personal lens through which they view any professional learning experience.

The second comes from the school (or trust) context that they are working in: A combination of policies, strategies, culture, resources and priorities – all coming together to create parameters within which that member of staff works.

These two sets of influences come together when each member of staff engages in professional learning. This means that even in a shared training session with their direct team, colleagues will each be experiencing and interpreting the CPD differently (for more on these “funnels of influence”, see Aubrey-Smith, 2020).

There are three distinct ways that this manifests itself:

- What colleagues say they will do: Often in conversation, on feedback forms or when disseminating to colleagues.

- What staff intend to do: Plans made during or immediately after a course or meetings set up.

- What staff act upon: Actions which immediately start to change practice for children or other colleagues.

It is important to note that whether the professional learning has an operational or a strategic focus, the nature of what happens immediately afterwards is what will (or will not) create an impact.

For example, saying that we will arrange a meeting to talk about something is very different from actually arranging that meeting. It is the latter which moves matters forward.

As such, for a colleague to shift from saying or intending to actually doing, we need to create an environment where staff are empowered to:

- Acquire new professional knowledge (through professional learning).

- Develop clarity about what needs to change (coaching, discussion, reflection).

- Have agency to change practices (decision-making abilities).

Therefore, as you plan professional development for and with your staff for 2021/22, you may wish to pause just for a moment and ensure that you are planning – from the outset – for staff to be able to act upon their professional learning.

The power to act: What should you consider?

So, for each colleague and for each professional learning experience that is being planned with them, I invite you to consider three things.

First, will this experience help colleague X to acquire new professional knowledge? How do we know what they already know? Therefore, how do we know that this will be new knowledge? How do we know what they want or need to know? Therefore, how do we know whether they will be open to learning this new knowledge?

Second, what support will colleague X need to help them develop clarity about what needs to change as a result of their new professional knowledge? For example, changes in their own practice? For their students? For other students in our school? For other colleagues? For our strategic work, policies or priorities?

Furthermore, how can we provide this? Perhaps via coaching, discussion with senior leader colleagues or peers, or via planned feedback or debriefs. Who should this be with? And does that person have the skills to coach colleague X towards clarity or will they assume ownership of the space themselves?

Third, how will you provide genuine agency – the ability to make meaningful decisions – to colleague X, so that they can act upon their professional learning and action plans? And who will support them to do so?

The final two parts of the checklist are often the two that are forgotten or not carefully thought-through. Yet these are the key ingredients for creating a collaborative and professional culture of meaningful learning across your team – ensuring that everyone is empowered to act upon their own (appropriately identified) professional learning (for more reading on this, see Priestly, 2019). After all, if we are not here to facilitate everyone to learn and then act upon their learning, then what are we here for?

Final thoughts

I wrote earlier this year in Headteacher Update about the seven Es of effective CPD (Aubrey-Smith, 2021b). Let me end by repeating from that article a reminder that effective professional learning should:

- Be sustained and with a regular rhythm of support over a period of two terms or longer.

- Be based upon a teacher’s own experience, needs and vision of what their children’s success looks like.

- Include opportunities to discuss with peers and “more knowledgeable others” both the theory and practice of new ideas, testing of ideas, seeing practices expertly modelled, and receiving of expert feedback on their own efforts.

- Be clear and explicit on the intended impact – on children’s learning.

- Dr Fiona Aubrey-Smith is director of One Life Learning, supporting schools and trusts with professional learning, education research and strategic planning. She is also an associate lecturer at The Open University, a founding fellow of the Chartered College of Teaching, and sits on the board of a number of multi-academy and charitable trusts. Read her previous articles for SecEd via http://bit.ly/seced-aubrey-smith and email fionaaubreysmith@googlemail.com

Further information & resources

- Aubrey-Smith: An introduction to the Funnels of Influence, February 2021a: https://bit.ly/2Qmqz6Z

- Aubrey-Smith: Evidence to Action: The seven Es of effective CPD, Headteacher Update, March 2021b: https://bit.ly/3dsivK7

- DfE: Early career framework reforms: Overview, last updated June 2021a: https://bit.ly/3y9ybdS

- DfE: National Professional Qualification Reforms, last updated May 2021b: https://bit.ly/3hrxV2e

- DfE: Early Career Framework, January 2019: https://bit.ly/3vqkRQc

- Priestly: Teacher agency: What is it and why does it matter? British Educational Research Association, September 2015: https://bit.ly/3dzQ50C