The humanities subjects bring with them the opportunity to learn about humans, about our world and our place in it, our interactions with cultures and religions, the marks we have made in the world, and the challenges facing us in caring for its future.

It is a rich and fascinating area of study, involving factual knowledge, conceptual understanding and the application of both to evaluate issues. It is filled with opportunities for critical reflection, evaluative discussions and collaborative planning, all of which requires competent and fluent command of the language of instruction. Language is at the heart of humanities subjects.

For some students using EAL, particularly those who are at the early stages of language acquisition, studying humanities subjects in English can be particularly challenging.

Standard 5 of the Teachers' Standards (DfE, 2011) stipulates that teachers should “be able to use and evaluate distinctive teaching approaches to engage and support” for EAL students. Distinguishing between language needs and learning needs will steer those “distinctive approaches” towards providing language support.

Lesson-planning

Although curriculum time may be restricted for non-core subjects, the humanities provide rich opportunities for developing language skills and simultaneously implementing truly inclusive practices. Rather than being a bolt-on, language should be at the core of lesson-planning. Jean Conteh (2019) asks that teachers consider:

- What we are expecting our pupils to be able to do with the language they are learning.

- The kinds of language they will need in order to do these things.

Learners engage with complex written and spoken language in every lesson. We expect them, for example, to compare regions in the UK with regions in other countries; to describe changes in physical geography over time; to make inferences and deductions about sources; to discuss links between cause and effect.

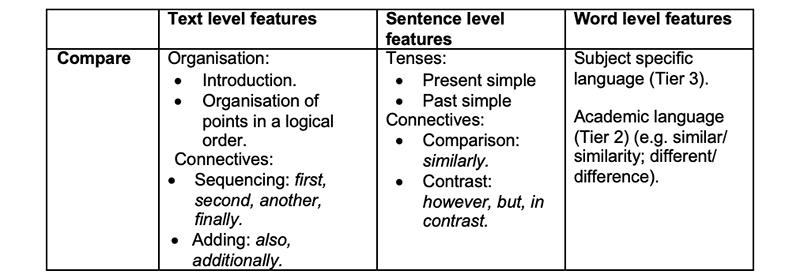

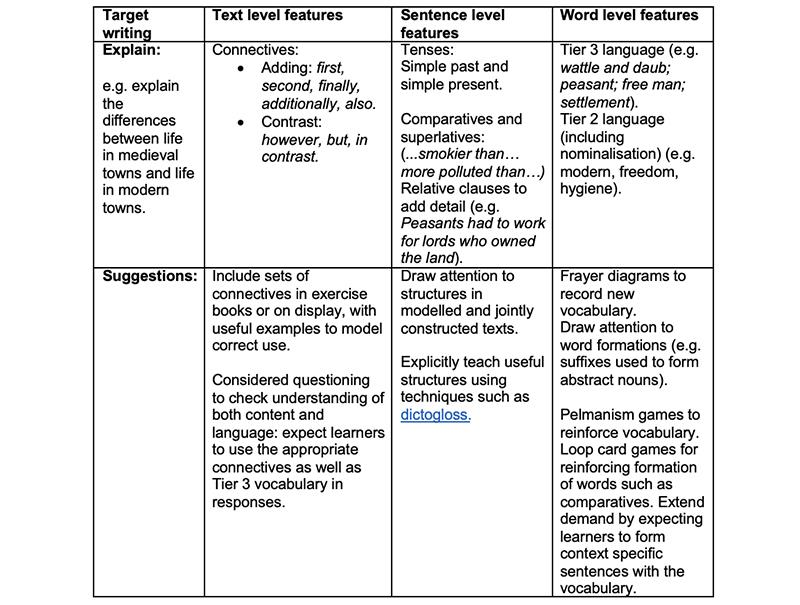

A useful way of planning for the kinds of language a learner will need to know is to break major activities down into the language features needed at a text, sentence and word level.

Once armed with an understanding of the language demands of a text or a task, class teachers might use adaptive strategies to help remove language barriers to accessing the curriculum. The rest of this article will consider adaptive strategies which might be used, and how they can be used. Many of the strategies outlined below are explored further in the Great Ideas section of The Bell Foundation website (for all links, see further information and resources).

Establishing the environment

Adapt the grouping according to the activity. Flexibility with groupings according to the learning intention can be effective.

Grouping learners by home language is useful where the focus is on learning new content. Although younger learners may not have strong literacy skills in their other language(s) it is still possible to make good use of the languages in their repertoire (known as translanguaging – see resources), for example to facilitate discussing concepts.

Meanwhile, grouping learners in mixed language groups is useful where the focus of activities is more on producing language to demonstrate understanding. Teachers can buddy learners who are new to English with supportive students who both understand the content and also model a good standard of English language.

Assessing knowledge of the field.

Assessing prior knowledge will highlight any gaps in conceptual knowledge and these will need to be addressed before the new topic begins. In assessing prior knowledge, it is important to distinguish between knowledge of language, and knowledge of subject.

Newly arrived students will bring with them subject-relevant expertise. Some students may already have the subject knowledge to “name and locate the world’s seven continents and five oceans” and so for them, the learning is more about language and less about knowledge.

Much learning will be transferable – an understanding of the differences between life in urban and rural areas in Nigeria, for example, will share some commonalities with a similar comparison in the UK, and could, in fact, be the source of a rewarding discussion.

However, strategies for assessing and activating prior knowledge will depend on proficiency in English. As simplistic as it may sound, getting to know the child and their family is a good starting place for building up a picture of prior knowledge. For more on the importance of assessing language proficiency, see this previous Headteacher Update article by Katherine Solomon article by Katherine Solomon.

Ideas for building knowledge of the field

Message abundancy (Gibbons, 2014), i.e. deliberately using multiple modes of communication to immerse learners in the key learning points, will increase the chances of meaningful learning taking place.

Pre-teaching: Some learners might benefit from having a head start before a topic begins, for example through the provision of vocabulary lists or back-filling useful language from previous connected topics. Where bilingual support is available, this would be a good resource to use to ensure a learner is at a similar starting point to their peers before the new learning begins.

Parental involvement: Families can be an excellent teaching resource but may need reassurance about using home languages. The Bell Foundation has produced translated guidance for parents (translated into 19 languages) on how families can support their children’s learning which schools may wish to share, in particular with families of new arrivals (see resources: Parental involvement). Project-based homework, for example, on religious festivals and how they are celebrated, will provide opportunities for the learner to be the expert, and in turn, provide enriching learning for the rest of the class.

Technology: Teachers can select the most appropriate aspect of technology depending on the learning needs of the students (see resources: Using ICT). For example:

- Translation apps such as Say Hi and Google Translate are useful where learners already know the concepts and only need to learn the language.

- Online monolingual dictionaries, such as the Free Dictionary and other first language websites (e.g. there are currently Wikipedia pages available in 312 languages), can enable learners to research a topic in their first language. Immersive Reader, in the home language, will support learners with limited first language literacy, as will home language videos.

Dual language materials: Providing translations of some aspects of a task will allow learners to clarify meaning and take a more active role in learning. Some dual language teaching resources are available on Twinkl for example. Mantra Lingua and World Stories are both excellent sources of dual language books, too. Dual language glossaries are available from websites such as Hounslow Language Service and EAL Highland, and these might be useful to share with families. Similarly, using Google Sheets is a very efficient and increasingly reliable tool. Including translations of concepts as well as key words in any glossaries will act as a reference aid for content as well as language.

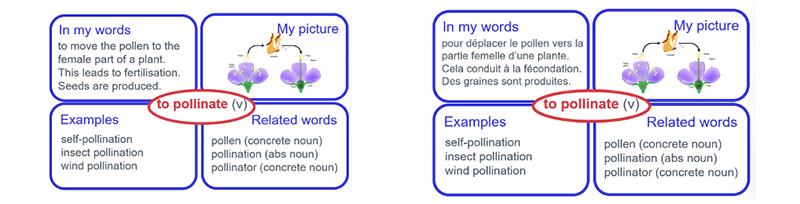

Explicitly teach vocabulary: Ideas for teaching new vocabulary (see resources), including how to make good use of a learner’s literacy in their home language(s), are well documented. For example, learners might be encouraged to use their home languages in Frayer diagrams.

Image: Designua/Shutterstock.com

Use visuals to reinforce understanding: Many aspects of the humanities subjects lend themselves to good adaptive teaching. There is an endless supply of visual material – photographs, maps, timelines, posters, videos, opportunities for speakers and school trips.

Communicative activities: Since producing the target language requires much deeper processing, activities such as barrier games (see resources) are a good way to consolidate understanding of new concepts/vocabulary.

Scaffolding (see resources): Barrier games with speaking frames or word banks will enable learners who are new to English to ask and answer questions in order to gather the missing information. Rather than adapting the curriculum content, we scaffold the language to increase access to the same content as peers. The key is providing the right amount of scaffolding – too little support and the learner is frustrated, too much support and the learner is bored. And either way, they make no progress.

Deconstruction and modelling

Disciplinary literacy is central to impactful subject teaching. Using modelling, explanations and scaffolds as the building blocks to gradually develop the skills to tackle a demanding text or a new style of writing will reduce the cognitive workload and allow learners to lay solid foundations for their learning.

Vocabulary choices: Teachers can activate links between informal vocabulary, typical of speech, and more academic vocabulary by recasting learners’ Tier 1 vocabulary choices:

- Student: Allah made the angels

- Teacher: That’s right, according to the Qur’an, Allah created angels.

Encouraging learners to eventually do this themselves, initially with the aid of word banks, will support the development of academic writing.

Provide model texts: By selecting texts which exemplify key structures, teachers can explicitly teach the language needed to fulfil the genre requirements.

Scaffolding: Substitution tables and writing frames can reduce the cognitive workload and support learners in producing the language. Some suggestions for meeting the language demands of a task taken from the key stage 2 history curriculum are included below:

Guided practice

Teachers can explicitly model written responses, drawing on all of the previous teaching, and then facilitate collaborative construction using structure strips or word banks appropriate to the topic and genre of writing.

Dictogloss is a good way to explicitly guide learners in structuring written pieces with the focus on the grammatical structures needed to demonstrate depth of understanding. The activity involves listening to the teacher and then collaboratively constructing a response before comparing it to a modelled answer.

Independent construction

Gradually removing the scaffolding and placing greater emphasis on peer reviews and then self-monitoring will support learners in moving towards greater independence in their ability to demonstrate subject learning. Learners who use EAL need to be involved in the editing of language content as well as subject content in order to take ownership of their language development and ultimately their academic attainment.

Wittgenstein (1921) may not have been thinking about how learners will access the curriculum, but the parallels are clear: “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

Caroline Bruce is training manager at The Bell Foundation, a charity working to overcome exclusion through language education. For details, visit www.bell-foundation.org.uk

Further information & resources

- Conteh: The EAL Teaching Book: Promoting success for multilingual learners, SAGE, April 2019.

- EAL Highland: www.ealhighland.org.uk

- Free Dictionary: www.thefreedictionary.com

- Gibbons: Scaffolding Language; Scaffolding Learning, Heinemann, October 2014.

- Hounslow Language Service: www.ealhls.org.uk/product-category/multilingual-support/

- Mantra Lingua: https://uk.mantralingua.com/

- Say Hi: www.sayhi.app

- Twinkl: www.twinkl.co.uk

- Wiitgenstein: Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1921.

- World Stories: https://worldstories.org.uk/

The Bell Foundation resources

- EAL Assessment Framework: https://bit.ly/3oNXmjM

- Great Ideas: https://bit.ly/3vbVD7J

- Parental Involvement: https://bit.ly/3AmRpN3

- Translanguaging: https://bit.ly/39z4bxI

- Using ICT: https://bit.ly/3coupUv

- Building Vocabulary: https://bit.ly/3HAvDtR

- Barrier Games: https://bit.ly/2HUd1Ll

- Scaffolding: https://bit.ly/2YrPTMa

- Dictogloss: https://bit.ly/3z5WsAS