This article introduces and discusses some of the findings from the research and systems that Earl Primary School (the school’s name has been changed to protect anonymity) put in place to challenge prejudice and to engage parents to participate in school life.

Earl Primary is an averaged sized primary school with a catchment area serving a broad mix of socio-economic backgrounds. Ninety seven per cent of pupils are of White British heritage. This school has actively worked to improve parental partnership, with interventions in place to support families with often complex needs.

Early intervention headache

Working as the headteacher of Earl Primary, an invitation was received to participate with colleagues from other disciplines in the Early Intervention Team. It was evident that the only children who could benefit and be supported in times of crisis were those children whose parents agreed to this support taking place. The restrictions this produced with regard to the help that could be offered to those children whose parents refused to engage in the early intervention process gave cause for concern. Parental support, partnership and equality of opportunity were core values of the school. As a result, questions emerged as to what degree parents were not “signing up” within the school setting.

This experience in the Early Intervention Team had a profound effect. I became rooted in the belief that early intervention offered a positive way forward for children experiencing social and/or educational difficulties, but that a key obstacle to making progress was the parents.

From my experiences as a class teacher, I had the belief that for a child to grow in their learning it is essential for the school to have a sound relationship with parents. A strategy was needed – the school had the fundamental beliefs and, in some cases, practices in place, but there was an absence of knowledge.

Parent partnerships

As a school, we needed to do better if we were to reach all the parents and not just those who were already engaging and cooperating. This led to a journey in pursuit of The Partnership Factor (figure 1).

There is a multiplicity of arguments within the literature (Campbell 2011, Ofsted 2015, DCFS 2008) referencing positive relationships and how they can improve outcomes for children and families. But how do we measure whether or not a “positive contribution” is taking place? The lack of evidence relating to methods of measuring the impact of parental partnership on attainment and progress led to the formulation of a system of measurement. A template was produced and developed in collaboration with teachers and parents.

A diverse team of professionals and parents worked together to formulate what they considered to be the key descriptors of parental engagement with the school and the child’s learning at home. A focus group of parents also formed part of the consultation process. The outcome was the development of a measured approach:

- To understand the impact of collaborative working on educational progress and attainment for the child.

- To better understand the long-term implications of parental partnership.

An original and significant contribution to the parental engagement literature is presented through developing a measurement tool to be able to categorise the partnership. The means to measuring the collaboration between the school and parents is through the creation of the Parent Partnership Descriptors or PPDs (Campbell, 2011). The descriptors identify four parental groups:

- Parent Group A (PGA): Those who meaningfully participate in the life of the school and most significantly their child’s learning.

- Parent Groups B & C (PGB & PGC): With reduced levels of involvement.

- Parent Group D (PGD): Little involvement with the school and often deemed as “hard-to-reach”.

The PPDs, once training has been provided to those implementing the system, have the potential to help the teaching profession to gauge and better understand the school and parent dynamic. The categories are used as a best fit. Teachers are advised that when undertaking an evaluation, the parent does not need to tick all of the boxes. Teachers are also advised that their assessments will be moderated. The application of the PPDs introduces a new dimension to the knowledge-base on collaborative working.

Pupil outcomes & challenges

The next stage was to analyse the level of correlation with a number of outcomes. Previous reports have demonstrated the correlation between parental participation and pupils who have SEND (Chambers, 2015). This study also identified the correlation with progress – children from PGD are disadvantaged in this area. This report will explore the correlation with additional potential barriers to learning which will include attendance, pupils in receipt of Pupil Premium, and those who are living in areas of deprivation.

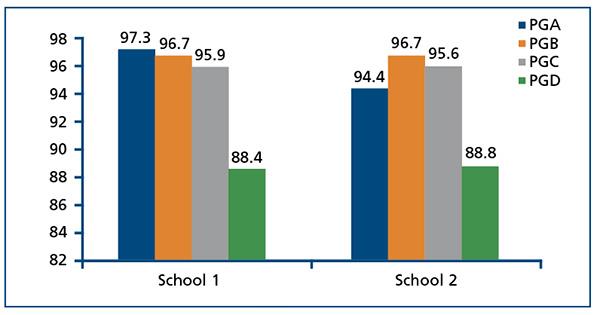

The first question to explore is whether this group is disadvantaged by poor attendance? With the help of a second primary school, the data shown in figure 2 compares the average percentage attendance achieved by pupils attending two different primary schools. The research was undertaken in 2017 and provided the first opportunity to test the PPDs in another setting.

Of note is the fact that PGD has reduced considerable over the years within school 1 (Earl Primary) and at the time of the study amounted to six children only. In a similar way, the number of children whose parents met the PGA criteria in school 2 was only eight (one PGA child in school 2 had an average attendance of 80 per cent which potentially skewed the figures).

However, the average attendance for PGD in both schools – 88 per cent – is perhaps a reflection of the descriptor for PGD: the parent who does little to support their child’s learning or the school.

The complexity of need

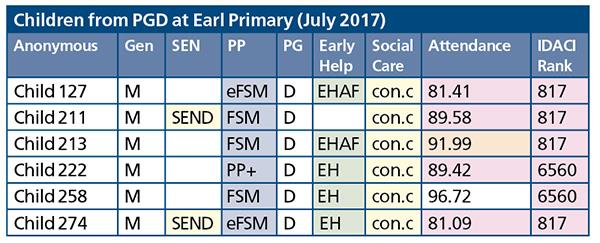

Remaining focused on the six children whose parents are categorised as PGD at Earl Primary, it is clear to see that individual children have a complexity of need.

Child 274 (shown in figure 3 below) has needed social care intervention (con.c refers to a confidential file being open) and the support from early help (EH) services. He is in receipt of free school meals and has SEND. His attendance is well below what is expected. In addition, the child lives in an area of high deprivation (in the top 10 per cent). Child 274 shows evidence of needing support across all of the areas. However, as can be seen in the table, all other children meet the criteria for five of the six risk factors.

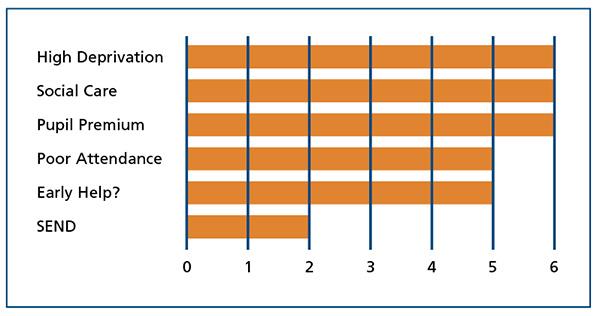

Figure 4 (below) shows how many each of the six PGD children have additional challenges to overcome. There are six potential risk factors included in the database as listed in figure 4. The complexity of need refers to how many of these risk factors individual children face.

As we can see, all six PGD children live in levels of high deprivation, they are all in receipt of the Pupil Premium and they have all needed social care intervention. Five of the six have poor attendance and five of the six have needed an early help assessment. Two have SEND.

Although the data-set is small, the complexity of need is evident. Some children move through their primary years with no other issues than the simplicity of developing their learning. It is difficult to ascertain whether or not this influences the parent’s ability to engage with the school or whether lack of engagement with the school leads to the need for additional support.

The complexity of needs has to be understood. Parents face many difficulties in trying to support their children (Reay, 2017) and doing so could prove to be a challenge if faced with one of the many risk factors, let alone all six. Reay (2017) argues that parental engagement with schools does not come easily – it has to be worked at and can be a real challenge. The additional barriers to learning need to be considered. In order to achieve this, it is imperative that a meeting be held with parents.

Parental meetings

The meeting has a clear purpose: what can we do to improve life chances for your child? The facts were shared and questions were asked. We discussed:

- This is where your child is currently achieving.

- Do you know that if he/she continues on this trajectory, they will not achieve well in their GCSEs?

- What do you want for your child?

Share the findings with parents, be honest and direct about where the child currently is. Then consider what the flight path could look like. The outcome from this conversation is the agreement on a way of working together, with both parents and leaders committing to improving life chances for the child. Meeting with parents, being direct and stating the facts led to a considerable reduction in the number of PGD families in school.

I began this research holding the parents responsible for a multitude of imperfections that were having a negative impact on the learning potential for the children – this is no longer my view. I believe that most parents want the best for their children but that there are barriers that need to be identified. Earl Primary aimed to ensure that parents were aware of the potential implications of their lack of engagement, with a clarity of how working in partnership with leaders could lead to these problems being tackled. The result was a decrease in PGD to two per cent.

The research set out to determine the impact of effective parental engagement with school and the correlation with life chances for children. The conclusions suggest that parental involvement has a correlation with a complexity of needs, meaning it is essential to establish a culture of learning in partnership as soon as the child starts school. PPDs, as an assessment tool, have been used to investigate and consequently establish a correlation between partnership and pupil academic outcomes (Chambers, 2017 – unpublished).

Without doubt more has to be done to educate parents and indeed primary practitioners of the benefits and the strategies needed for working in partnership. While this research is small-scale, the messages are clear.

- Donna Chambers was a headteacher for 13 years, leading two very different primary schools. She has spent the last year broadening her experiences, working in a number of London schools. Donna sees children whose parents do not engage with school as a vulnerable group and improving these partnerships forms part of her doctoral research.