The use of technology in schools has never been under more scrutiny than it is right now. The key focus of any scrutiny is, of course, impact. Is the technology used having a positive impact on learning outcomes, attainment, and pupil development? And how exactly is that positive impact being facilitated by technology?

There are frameworks to help measure impact of the use of technology and this article looks at one such model in order to assess its effectiveness in application.

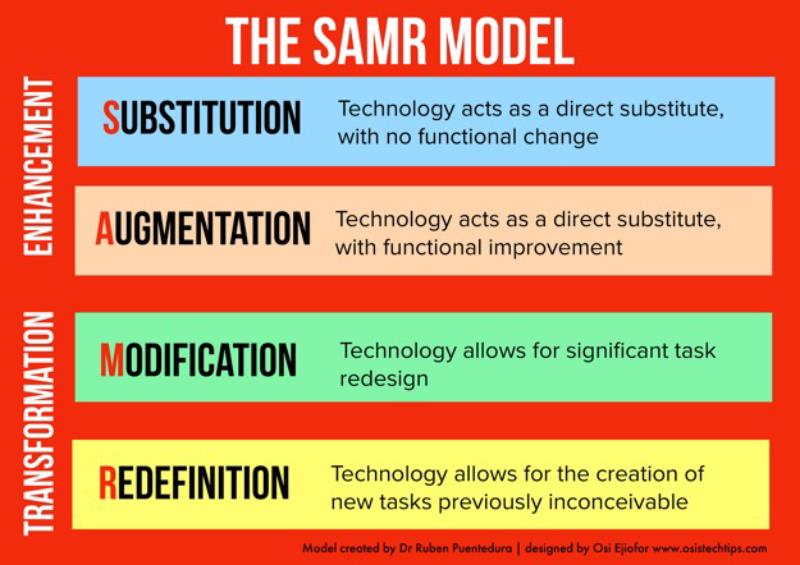

The SAMR model is a framework for the integration of technology in the classroom. It is an acronym (of course!). It stands for Substitution, Augmentation, Modification and Redefinition. It is split into two categories – enhancement and transformation – which categorise how technology is affecting learning.

The model was created by Dr Ruben Puentedura in 2010 based on his analysis of how technology was being used to improve teaching and learning in the classroom.

The SAMR Model: This approach helps schools to understand how technology is being used in the classroom (Puentedura, 2010)

Enhancement

The first two letters of the acronym fall under the enhancement category: namely substitution and augmentation. These types of edtech use suggest that learning has somehow been enhanced by the use of technology.

Substitution practice is when the technology being used is directly replacing analogue methods and no functional change has occurred in the learning outcome. Examples of this would be:

- Typing a report rather than writing it.

- Using a tablet device and stylus to record notes or solve equations rather than pen and paper.

- Taking a quiz online.

- Completing a digital worksheet.

- Reading a digital book.

Augmentation, meanwhile, builds on the substitution level by incorporating elements that improve functionality of the learning that is taking place.

Examples of this would include:

- Creating a slideshow presentation that includes hyperlinks to further information.

- Creating an ebook with embedded video clips.

- Online research.

- Video instructions for students.

- Asynchronous lesson instructions.

Transformation

The final two letters of the acronym fall under the enhancement category: namely modification and redefinition. These are the stages at which there is both significant task redesign and a use of technology that facilitates learning (without which learning would be inconceivable).

A modification task would include elements such as:

- Online collaboration on a task for research or content creation (docs, presentations, etc).

- Verbal marking using voice notes within a document for student feedback; notes that can be played back by the student and are not restricted to location.

- The use of virtual reality to visualise learning concepts, go on journeys, contextualise experiences, etc.

- The simulation of predicted outcomes.

- Creating a web page of learning evidence that can be kept during a students’ time at school and used to support other learning, parent engagement, etc.

- Augmented reality being used to analyse learning concepts in three dimensions.

- Remote communication, such as video-conferencing, with other classes or students in locations around the world.

- Simulation of workplace experiences using similar or identical technologies.

- Technology being used in PE to analyse motion or for biomechanical analysis by students.

- Creating an animation using voice narration to teach learning concepts.

Redefinition tasks, meanwhile, see learning taking place that would not have been possible previously without the use of technology. These might include:

Misconceptions about using the SAMR model

In comparison to other models, such as TPACK (Technological, Pedagogical and Content Knowledge), the SAMR model may appear to be less complex, easy to understand and easy to put into practice.

However, its apparent simplicity could be the reason why there are some who misunderstand the purpose of the model and thus how it can be applied to improve technology’s effectiveness in relation to teaching outcomes.

These misconceptions tend to centre on some seeing the S and M stages as “bad” and thinking that all technology-use should be at the M and R level.

A lack of learning-centred process towards developing practice from the S and A stages towards the M and R levels can lead to a desire to see technology being used at a more advanced level without truly exemplifying the M and R stages.

For example, a lesson that shows students coding to create a website may seem to demonstrate redefinition, but if the students are copying and pasting code following simple instructions then the learning taking place is similar to copying a book onto paper. The learning journey is not redefined but substituted with elements of augmentation.

We must understand that the model is descriptive rather than prescriptive and should be used in order to identify where practice is, before considering how to develop plans towards deeper, meaningful learning experiences and outcomes.

The model should be used as a tool to clarify our use of technology in comparison to our intended learning outcomes and pedagogical approaches.

Its use should take into consideration the level of experience of the practitioner, the experiences of the students, classroom culture and other factors that affect the learning experience.

This should result in a more considered, patient approach towards demonstrating good examples at each stage. In the coding example above, this could mean we would have a lesson plan that contains elements of interactivity and creativity that redefine pupils’ learning experience. It may not be coding that is the focus but rather the design process and methods of communication used to convey the learning.

There are no fixed Levels of SAMR

There would have been a time in the 1920s in which there was scepticism around the idea that slates would no longer have a place in the classroom.

According to the SAMR model, use of paper and ink would be identified as being at the S stage. Work books would be at stage A.

Perhaps in the present day we would assess word processing as S, but a time will come when it is standard practice and therefore not considered to be a “substitution” anymore.

With this in mind, it is good to be aware of our identification of technology-use at each stage considering that technology is not static. What is identified as R in 2021 may not be R in 2030. What is identified in one setting as S may not be in another due to the robust infrastructure and common use of technology in that setting.

There is no point of arrival, but rather continual assessment of the impact the tool is having on the intended learning journey.

Continual review of applications, hardware and software is useful to ensure that learning experiences remain impactful. What was redefinition may not be so in time. Advancements in tech, student ability and other factors will contribute towards this transition, too.

Correct use of SAMR

Considering the above, effective use of the SAMR model would be an approach that analyses the model carefully and identifies clearly what constitutes technology use at each level for your setting.

There would then be consideration of where your teaching staff are regarding confidence levels when it comes to using technology in their subjects. There also needs to be an understanding of their pedagogical and content knowledge if we are to identify where to focus CPD when aiming to improve edtech practice.

Taking for granted infrastructure and access to software and hardware, an effective approach would use the model to review common practice throughout the school. These findings would then be used to help practitioners improve their students' learning journeys and outcomes.

Our aim must be to outline clear, individualised steps at a manageable pace to embed new practice and develop confidence in the use of technology.

Above all, there should not be a punitive approach, where certain stages are not evidenced, but rather consideration of what the intended learning outcome is in that context.

For example, an English lesson in which the students are asked to read using a device should not be expected to have elements of M and R for the sake of demonstrating “excellent practice”. It may be that this use of technology is the most appropriate for the lesson and it doesn’t require anything more.

Enhancement stage evidence is not “bad” and transformation stage evidence is not “good” – they are merely identifiers of what can be seen, descriptive as opposed to prescriptive.

The learning that is taking place should always be at the centre of the intended use of the model. If we approach SAMR with this mindset, I think there are benefits from using the model.

I understand that there are time constraints on all of our colleagues, but I believe that taking time to fully understand frameworks such as TPACK and SAMR – which I believe actually work best together – will help us transform learning experiences and outcomes when using technology in the classroom.

- Osi Ejiofor is an education technology teacher trainer and has worked in primary education for more than 14 years. Follow him @osistechtips or visit www.osistechtips.com

Further information & resources

- Puentedura: You can access Dr Ruben Puentedura’s blog, which includes a number of entries relating to the SAMR model, via http://hippasus.com/blog/

- TPACK: For more on the TPACK framework, visit http://matt-koehler.com/tpack2/tpack-explained/