It is rush hour in London and you are about to experience the Underground, for the first time. The train is jam-packed. Smells turn your stomach. The noise of unintelligible people is your “nails down a blackboard” sound. The doors shut squishing you in and the ground begins to wobble violently. Are you on the right train? How long will this ordeal last? You look around for a visual map to count down the stops.

Imagine if arriving at school felt the same as getting on that Underground train. Autism spectrum conditions (ASCs) can intensify sensory experiences, heighten anxiety, and affect communication and social skills. It is up to us to observe, find the cause of anxiety and improve the child’s emotional journey. Every person with autism is different and autism can partner so many other conditions, which will affect learning.

A child may have autism and dyslexia, autism and ADHD, autism and learning delays or autism and giftedness. The list goes on. So where do we start? Here are my top 10 tried and tested strategies to support learners on the autism spectrum.

Motivate the individual

What gets those commuters on a jam-packed train in the first place? They want or need to get from “a to b”. Think of the school day as one long journey. Lessons are individual trains caught during the commute. What is the incentive? Are we meeting a “want” or a “need” in the child? Do they see the point? Is there any way you could adapt so that they feel more accommodated, motivated or in control?

What if the class was a little quieter, a little less crowded or a little more predictable? What if someone happened to be demonstrating the latest mini-robot (your student LOVES robots)? Think Pied Piper tactics. How did the Piper get the children to follow him from Hamlin? He played their music.

Provide a schedule

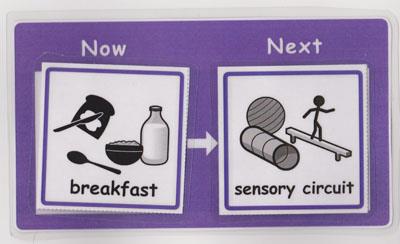

Compare the schedule to the map on the train. It is providing vital information about the day. How long until playtime? How long until lunch? Routines and repetition make us all feel safe. A child may need an individual visual schedule if they have different activities on their timetable.

Try to keep familiar structures and give advance notice if there will be a change. It is not only what is happening during lessons that is important. Other things, beyond teacher control, may be the difference between a good or bad day: “What’s for lunch?” “Will rain mean no football at playtime?”

Knowledge helps the child with autism to mentally prepare themselves, avoids disappointment and builds trust.

For some children we break the schedule down further with a visual “Now and Next” or “Now, Next and Then” board (pictured above). We may need to break down our lessons further with schedules for activities (pictured, below).

We use what the child will understand. Maybe they will need to sit for a story then carousel between four activities. We must set expectations so that the child can succeed at their pace. Ten minutes sustained attention has more value than 30 minutes of anxiety.

Bridging transitions

Lack of structure and movement create noise and can heighten anxiety. Provide a structure to transition times (maybe the child could look at a book or bounce on a mini-trampoline).

Taking a symbol from a visual schedule and placing it on a transition board (pictured) can help the child with autism with the transition between activities or areas because they see the transition as a matching task. There is a clear point. They match the red table symbol to the red table transition board and suddenly they are in the right place.

Using visuals reduces verbal clutter. Some children find demands difficult. Following someone else’s agenda reduces their control and creates anxiety. These children can transition, but they need a creative teacher so that they don’t feel transitioning is a demand. Planning and preparation are also essential to support transitions to a new class or new school.

Add structure

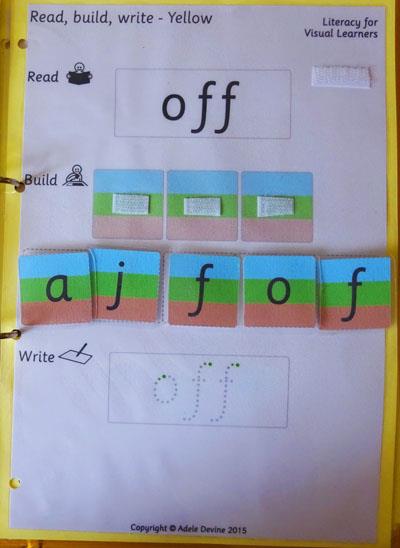

Tasks and activities should be broken down so that the stages are clearly mapped. Allow a child to master new skills through repetition.

An activity that requires skills they have not yet perfected (such as handwriting) might feel impossible or overwhelming. The child may not see the stages in learning and they may fear failing.

Provide achievable tasks with a set structure (pictured) and the child with autism will see that they can “have a go”.

As we build trust they will begin to stretch themselves, but we must gauge individual pace. Also ensure that the tasks either have a functional purpose or are related to their motivators (ideally both).

Use rewards

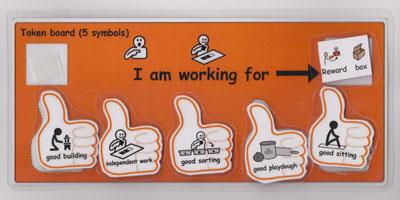

We all like rewards. A reward might be a choice from a reward box or additional playtime. We may need to use a reward board or token board (pictured). Reward boards are most effective when they show exactly what tokens are for.

Take care with whole class reward systems as your student with autism may be fiercely competitive and like to be first.

Never remove a reward earned and listen if they suggest an injustice. Whole-class punishments are a huge “no”. We can add to playtime as a reward, but never threaten to remove it.

Give them time

How long is the activity going to last? The child with autism may be struggling with sensory issues and anxiety will intensify these. They will not want to waste their time.

Studies have revealed that children with autism are most likely to miss out the unnecessary steps when given a task. These children might not simply follow because something is on your plan. They like to know why and they like to know how long.

Provide a visual way to show time elapsing – a time timer, sand timer or adapted clock. Add timer symbols to schedules. Be aware that the child may process differently. They may not respond as quickly.

Meet sensory needs

Children with autism may see things differently, they may experience pain from sounds that we do not notice or they may be highly sensitive to touch. Anxiety will heighten these sensitivities. Maybe one day a child can sit in the canteen, but the next day there is a different smell or earlier demands have reduced their ability to cope. We must give them time and try to see through their eyes.

A child with autism may need more physical activity built into their day. They may need to twiddle or seek comfort from deep pressure. Be aware and prepare to support these differing needs.

Prepare for change

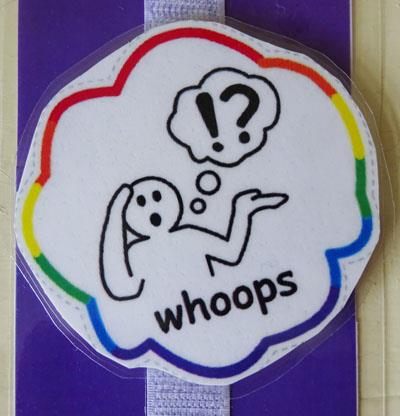

Things do not always go to plan. Maybe PE is replaced with a play rehearsal or a broken down coach prevents an outing. Prepare the child in advance by teaching them that a “Whoops!” is a part of life.

We build these into the day so that the unexpected becomes a part of our routine.

We all like structure and routine, but life does not always follow set plans and it is up to us to teach coping strategies.

Improve communication

Establish open communication with parents early. Find out what motivates the individual child, what triggers anxiety and what they are like at home? A phone call tells parents that you care and that they can reach out if they need support.

Many parents will say that “homework is an absolute nightmare” because the child does not see school work as a part of their home routines. Work with the parents on these things and you will make such long-term differences.

I recall working with a boy who found homework overwhelming. Together we made a list of what he needed to do and he decided when he would like to schedule a break.

Following TEACCH (Treatment and Education of Autistic and Communication-related handicapped Children) structures we put all the work on the left and had a “finished” tray on the right. Adding these structures to homework made such a difference. It was no longer “a nightmare”.

Opening communication lines with the headteacher can be really effective. Have a school post box where children can send a letter to the headteacher if something has caused them stress, made them angry or uncomfortable. Posting the issue and feeling they have been able to express it can be a huge relief.

Use the child’s name so that they know when your talking relates to them. Speak directly and clearly with a consistent, controlled volume. Never shout. If the child does not yet speak then provide the means for them to communicate their way using a Big Mack switch, an app on a tablet, PECS or PODD books (search online for more information on these).

Build their trust

Be consistent, be fair and listen. Love what they love. Create a calm, uncluttered space where they feel safe. Keep your promises. If you say an activity will finish in five minutes then stick to it.

Conclusion

Sir Isaac Newton (who like many of our brilliant innovators has been posthumously diagnosed with autism) once observed, “we build too many walls and not enough bridges”. When it comes to teaching children with autism we must continually build bridges. Be aware of the sensory issues and anxieties that often partner autism. Take the time to observe and listen and you will start to see and respond in a whole new way.

- Adele Devine is a teacher at Portesbery School, an all-age day school (2 to 19) in Surrey catering for children and young people with severe learning difficulties. She is the author of Colour Coding for Learners with Autism, published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers, and was a finalist in the Award for Achievement by an Individual Education Professional category at this year’s Autism Professional Awards run by the National Autistic Society.